For Roman Opalka, 1965 marked the beginning of time. At the age of 34 (arithmetic mine), he picked up a brush and painted the number 1 in the top left corner of a large canvas. He proceeded to document the passage of time by counting - left to right, top to bottom - until each canvas was full, continuing on the next and so on until he reached infinity or met his end trying. Spoiler alert: it was the latter. But this unrelenting persistence, this simple act of defiance against the inevitable forward march of time was, in my opinion, one of the great romantic performances of the 20th century.

Opalka titled this series of works Opalka 1965 / 1 - ∞. Each canvas, called a Détail, measured 196cm high by 135cm wide - the artist’s height and the width of the door to his studio. When he traveled, he continued counting with ink and paper in another series, Cartes des Voyage. The first million numbers were painted white on dark ground. Instead of reloading the brush for each number which would ensure consistency in each stroke, Opalka painted until his size-zero brush was empty before going back for more. As I moved across the canvas, the strings of numbers glimmered back at me like starlight bouncing enigmatically on a sea of waves.

Roman Opalka, Opalka 1965 / 1-∞, Détail 1-35327

Acrylic on canvas, 196x135cm. Museum Sztuki, Lodz

After he reached 1,000,000, Opalka began lightening the ground of each successive canvas by 1%, envisioning a point in the future when white numbers fade entirely into white canvas. A sort of pure end – or beginning, perhaps. I’m reminded of the Qing dynasty novel, Dream of the Red Chamber, which ends its saga depicting the long and arduous deconstruction of a powerful family with the phrase, “白茫茫大地真干净” – “a land of all white is so clean.”

Roman Opalka, Opalka 1965 / 1-∞, Détail 4875812-4894230, 4894231-4914799, 4914800-4932016

Acrylic on canvas, 196x135cm. Christie’s.

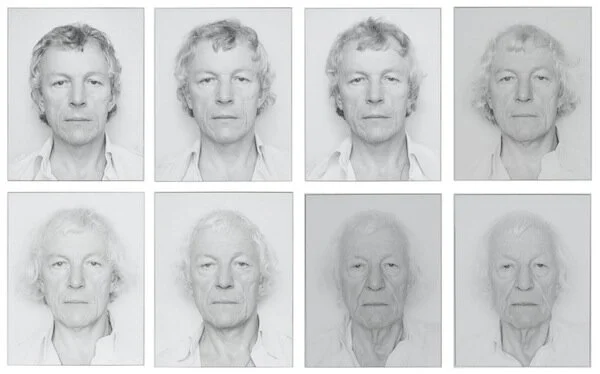

In 1968, Opalka added another element - photographing himself at the end of each day in the same position, clothing, lighting and expression in order to document the effects of time on his face as accurately as possible. Describing one particularly difficult consequence of this commitment, Opalka recounted:

It is not easy to set aside one’s own preoccupations to achieve the same expression every time. The most dramatic moment was probably the day my father died. I had to fight against the intensity of my feelings to submit to sitting for this horrible photograph.

Opalka made one final addition to his process in 1972: recording himself speaking each number in his native Polish as he painted them. This would later become important in proving his personal execution of each piece.

What struck me about the process was the idea that time both belongs, and does not belong, to us. Opalka chose to remove himself from the creation of his works by defining initial boundary conditions that were independent of his influence: counting numbers, mechanically reloading his brush only when it was dry, lightening each next canvas by exactly 1%, and photo documenting himself as a time-lapsed object. But in other ways, his work contained himself, intimately and completely. Each number was painted by his own hand rather than block-printed like in the work of his contemporary, On Kawara. The dimensions of each canvas were determined by his height and the width of his studio door, as if to quietly whisper that each installment was the embodiment of his life and the moment he crosses the threshold to another world. Finally, by speaking each word in his native tongue, he took a number, whose concept and representation are universal to all languages and people and made it distinctly his.

This dichotomy is rooted in the story Opalka told of his childhood where one day, while enraptured by his family’s large pendulum clock, it suddenly stopped working:

Catastrophe: my parents will find me guilty. I stared at the pendulum for I don’t know how many minutes or hours, with the idea that I could get it working by will power alone, through the intensity of my gaze. When my mother came in, she didn’t even see my tears and my puffy face: she went straight to the clock. She wound it with a key and the world started ticking again.

In 2011, at the age of 79, Roman Opalka painted his last number: 5,607,249. François Barré recalls a conversation with the artist when he said, “the last Détail, probably incomplete, will in fact be the only painting that is truly finished because when it ends my concept ends.”

It’s interesting to note that it belongs to a set known as Queneau Numbers, after the writer Raymond Queneau, co-founder of the Oulipo (Ouvroir de littérature potentielle) movement in 1960. The Queneau Numbers are defined as numbers n such that the permutation is of order n. In other words, start with a number n and its corresponding sequence and draw a spiral working toward the center, reordering the numbers in this manner. A number n is a Queneau Number if it takes n cycles of reordering to return to the original sequence. In this case, 5 is a Queneau number because it took 5 spiral permutations to return to the original sequence.

This is a known technique of cyclic poetry where words are reordered by certain repeating rules. While there is no evidence that Opalka was even aware of Queuneau numbers, let alone intentionally concluded his life’s work with one, I’m tickled by the possibility that a man who devoted his life to representing the unwavering forward passage of time by counting numbers might have made a private joke, ending his epic journey with a number that cycles back onto itself by scrambling its count. After all, we must still recognize that the task of counting to infinity, and I say this with great reverence for the artist and his achievement, carries with it an appreciable measure of charming absurdity in and of itself.

Opalka was heavily influenced by Władysław Strzemiński, one of the founders of Unism, who introduced him to the phenomenon of “powidok,” which in Opalka’s words is, “an untranslatable Polish word meaning what is left inside of you after having seen something that profoundly affects you, a sort of ghost inside you that becomes an unconscious memory yet changes your aesthetic language.” I left the gallery that day with a feeling deep inside me that can only be described as powidok.

-MM